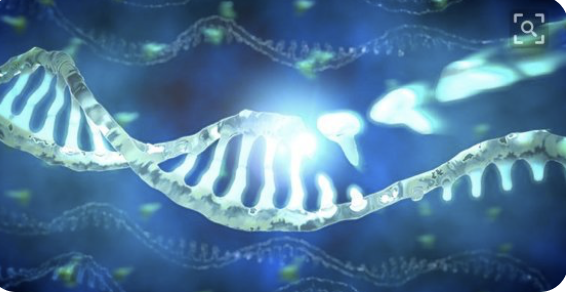

DNA data storage is regarded as a Technology Landmark for use in an OmegaMap. It is estimated that 160 zettabytes per year storage capacity will be required worldwide by 2025.The information presented here is based on an article “The Rise of DNA Data Storage” written by Megan Molteni and published in Wired on June 26, 2018. This article cites many sources, but focuses on the work of Hyunjun Park at Catalog Technologies.

The locus of innovation is a new Principle of Operation embodied in a system using the code for of DNA (symbolised by the letters C G A and T) as well as the carrier for this code as well (four nitrogen containing nucleobases (cytosine, guanine, adenine, and thymine). This is a step beyond present data storage devices such as magnetic tape, silicon chips, hard disc drives and flash memories. In these cases the code and the carrier are two separate elements.

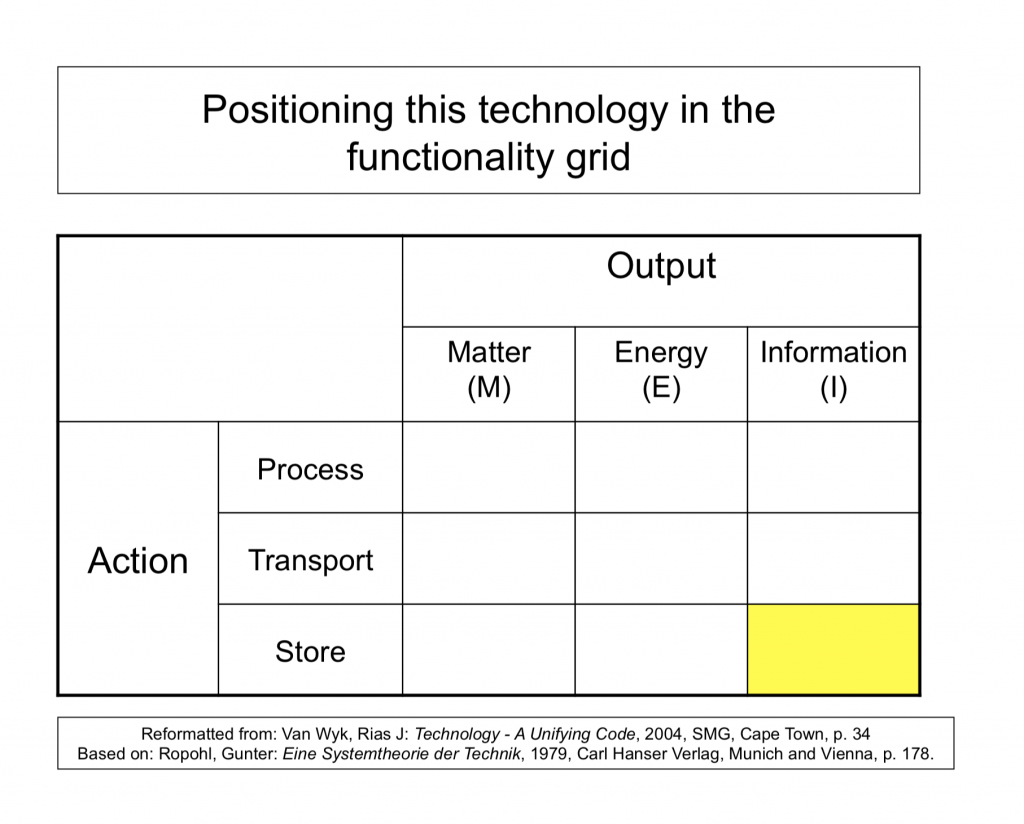

The effect of this innovation is to improve the Functionality : Store-Information. Its position is indicated on the Functionality Grid. (See diagram below).

Three Functional Performance Metrics are recorded. (i) Data stored per unit of space. At present hard disc drives store approximately 30 million gigabytes per cubic metre, while the potential for DNA is 600 billion gigabytes in the same space. (ii) Duration of storage. Hard disc drives need to be refreshed once in five years, tape has to be replaced after ten years, while DNA is stable over millennia. (iii) Energy used to store a unit of information. Details are not available but present data storage centers require as much electricity as a medium sized country. The functional performance metric for DNA storage is orders of magnitude less.

The Technology readiness level on a scale of 1 to 9seems to be TRL3 : i.e., “Experimental proof of concept”.

Technical terminology is covered in: Van Wyk, Rias, (2017) Technology: Its Fundamental Nature, Beau Bassin, Mauritius, LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, (http://amzn.to/2Avsk3r)

For descriptions of:

- Technology Landmark; pp. 83-84, Diagram 11.1, Stage 3

- Principle of operation; p. 20

- Functionality; pp. 24-25

- OmegaMap; pp. 92-93

- Functionality Grid; pp. 29-32

- Technology readiness levels; pp. 22-23